In 1938, three years before his death, the legendary Jelly Roll Morton sat down to record a series of Library of Congress interviews with noted folklorist Alan Lomax, who called the results “a virtual history of the birth pangs of jazz as it happened in the New Orleans of the turn of the century.”

Along the way, Morton elaborated on his narrative with various songs, including one he called “Winin’ Boy Blues,” a tune that contains more anomalies than a Salvador Dali canvas.

You can start with the song’s authorship. Some credit Morton as its composer, perhaps as a musical tribute to himself. Others believe Jelly Roll heard it in his youth as a folk tune about the sportin’ life in his native Crescent City.

What About the Title?

Then there are the questions about that title. Transcripts of the original Lomax interviews preserve the song as “Winin’ Boy Blues.” Subsequent recordings, however, have called it “Whinin’ Boy,” based on what later listeners think they hear Morton actually saying in the audio of those interviews.

Each opinion has its advocates.

The “Winin’ Boy” school of thought contends “winin’” is a double contraction of the word winding, the term presumably meant to celebrates the sexual dexterity of the song’s protagonist.

A smaller — and perhaps less convincing — class of followers in this same group think “winin’” refers instead to the boy’s love of wines. Some even go so far as to suggest the song’s boy got his name from his habit of collecting all the near-empty wine bottles after a night's debauchery, pouring them together into one glass and drinking it down.

Meanwhile, on the other side of the debate, commentators contend the word is “whine” because a whining boy, they say, is old New Orleans slang for a pimp. Or, in a variation, that he was a youngster who sat outside a brothel with his guitar and/or harmonica or just his voice; then when he saw police coming, he would "whine" a specific song/tune as an alert to the people inside the house.

Take your pick. Wind, wine or whine.

Don’t Deny

The music’s mysteries don’t stop there. Morton’s opening lyric is:

I'm the W(h)inin' Boy, don't deny my name.

How does a name get denied? And why? And by whom? The good folks over at the Internet’s fun Mudcat Cafe (mudcat.org) have had wonderful discussions on this bit of verse.

A contributor known only as “Amos” noted, “Having your name ‘denied’ (denigrated or made nothing of) is part of the general burden of debasement that blues like these are born in.

“Similar complaints from other parts of the forest,” he added, include: “Just 'cuz I'm a stranger, everybody wanna dog me around…” (e.g. Howlin’ Wolf).

Stavin’ What?

At least one more of the song’s curiosities calls for exegesis. Lower in the same opening verse, Jelly Roll growled:

Pick it up and shake it like sweet Stavin' Chain.

Like, uh, say what?

Well, let’s start with the fact that there was an actual tool called a “staving chain” used in the old days of barrel-making. It was a length of chain with a loop on one end (like a dog choker collar) used to pull the staves of a barrel together so that the hoops could be driven in.

“Stavin' chain” also popped up in prison culture as the name of a similar chain pulled around inmates’ ankles to hold chain gangs together.

And, as you might imagine, we once again are not far from sex in this search. A much smaller stavin’ chain — made of little smooth links — was said to be used as a sexual aid to help a man "stave off" ejaculation during a frolic. (We’ll just leave it at that and let you and your vivid, virile imagination take it from there.)

Stavin’ Who?

By the way, in the Lomax interviews, Morton noted that “Stavin’ Chain” was not only a what but a who. “Stavin’ Chain” was the name of a pimp, he said, who was “supposed to have more women in this district than any other pimp.”

As a trickster in African American legend, “Stavin’ Chain” figures prominently in later recordings by Lil Johnson and by Big Joe Williams.

A 1937 Johnson recording, for example, identified “Stavin’ Chain” as the chief engineer on a train, a big, strong man who could make love all night long. In 1939 when John and Ruby Lomax were recording songs by prisoners at Ramsey State Farm in Brazoria County, Texas, they found at least two different inmates claiming to be the original “Stavin’ Chain.”

Footnote: Oh Mary…

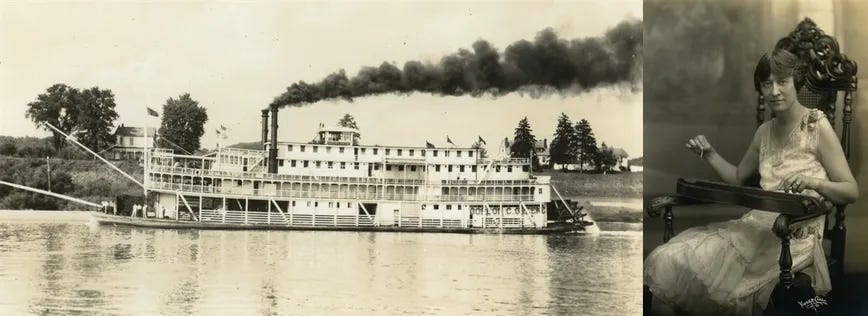

Oh, and if you remember our earlier discussion of Kentucky-born musicologist Mary Guthrie Wheeler, who wrote 1944’s Steamboatin’ Days: Folk Songs of the River Packet Era, you might get a kick out of knowing of her unintentionally hilarious difficulties in trying to collect a version of "Stavin' Chain" for her book.

You got to wonder what wizened old stevedores thought when she approached, in all innocence, asking them to sing to her about this “stavin’ chain” she had heard so much about.

Our Take on the Tune

Whatever its mysteries, Jelly Roll Morton’s tune has always resonated with us.

We love how this century-old song just eases on down and settles into a groove on any sultry summer night.

And, hey, here’s a shout-out to Floodster Sam St. Clair. We seldom can accompany these weekly podcasts with video, like the one that tops this report. We’re grateful that Sam happened to have his camera running when this tune got played at a recent rehearsal.

Share this post