Folklorist John A. Lomax found this song in 1909 when he made his first field trip to the Brazos area of Texas for Harvard University.

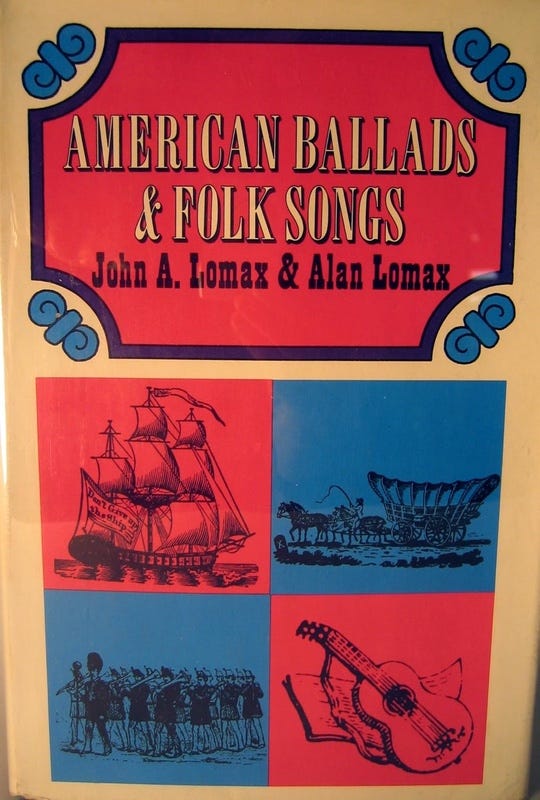

“I found Dink scrubbing her man's clothes in the shade of their tent across the Brazos River from the A. & M. College,” Lomax wrote when he and his son Alan published the song 25 years later in their seminal 1934 work, American Ballads and Folk Songs.

Harvest Professor James C. Nagle had been the supervising engineer of a levee-building company during that first trip, and he invited the senior Lomax to come along and bring his new Edison recording machine.

Among the levee workers who had traveled from Mississippi to work on the Brazos, Lomax found one who pointed out Dink, saying she “knows all the songs.”

But Dink was uninterested in helping — “'Today ain't my singin' day,” she said — until “I walked a mile to a farm commissary,” Lomax wrote, “and bought her a pint of gin. As she drank the gin, the sounds from her scrubbing board increased in intensity and in volume. She worked as she talked.”

“That little boy there ain't got no daddy an' he ain't got no name,” Dink told Lomax. “I comes from Mississippi and I brung along my little boy. My man drives a four-wheel scraper down there where you see the dust risin'. I keeps his tent, cooks his vittles and washes his clothes. Some day I gonna wrap up his wet breeches and shirts, roll 'em up in a knot, put 'em in the middle of the bed and tuck down the covers right nice. Then I'm going on up the river where I belong.”

The Tune

Lomax’s original record of “Dink’s Song” — which the storyteller eventually sang for him — got broken long ago, but not before John, Alan and others in the Lomax family all learned the words and melody.

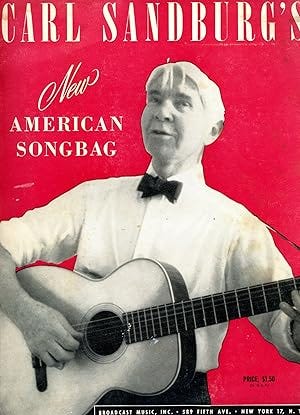

Poet Carl Sandburg, who included the song in his New American Songbag in 1950, compared Dink’s lyrics to the best fragments from the Greek poetess Sappho. “As you might expect,” Lomax commented, “Carl prefers Dink to Sappho.”

The elder Lomax lost track of Dink after his 1909 field trip. "When I went to find her in Yazoo, Mississippi, some years later,” he wrote, “her women friends, pointing to a nearby graveyard, told me, ‘Dink's done planted up there.' I could find no trace of her little son.”

The first commercial recording of “Dink’s Song” came eight years after the Lomaxes published it in their songbook, when Libby Holman waxed it as “Fare Thee Well” in a recording with Josh White for Decca Records.

Oh? You say you don’t know who Libby Holman was? Oh boy, do we have a story for you!

Libby’s Life

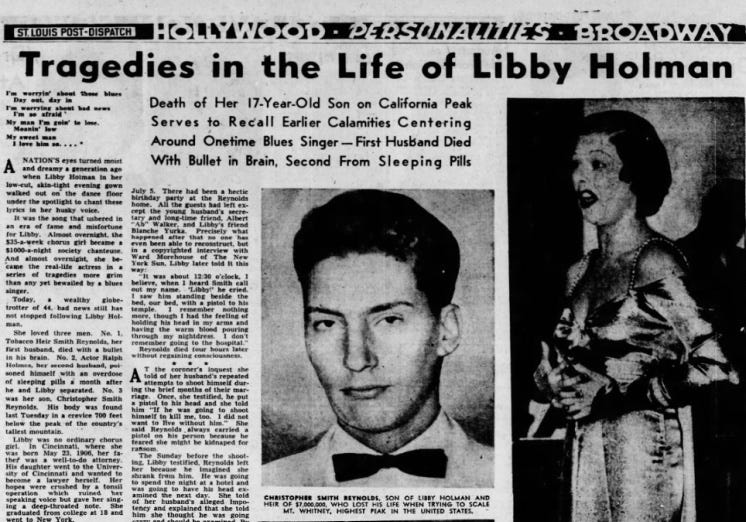

A Cincinnati-born actress and singer — her career began as a torch singer on Broadway in the 1920s and ‘30s — Libby Holman was a controversial figure, known for her turbulent personal life as well as for her activism, which included unstinting support for civil rights.

When she was in her late 20s, Holman was at the center of a highly publicized case surrounding the death of her first husband. Zachary Smith Reynolds, heir to the R.J. Reynolds tobacco fortune, who died of a gunshot wound at their estate in 1932.

Initially, Libby was accused of murder, but the charges eventually were dropped. The coroner ruled Smith’s death a suicide. For her part, Holman said she couldn’t remember exactly what happened, telling a friend, “I was so drunk last night I don't know whether I shot him or not.”

Relationships

Holman was known for her intimate affairs with both men and women, including a significant relationship with DuPont heiress Louisa d'Andelot Carpenter. The tabloids of the day had a ball with Libby’s openness about her bisexuality.

Folk/blues artist Josh White also has a significant professional and personal connection with Holman. In the 1940s they became the first mixed-race male and female artists to perform together, to record together and to tour throughout the United States.

Together they challenged segregationist policies in the entertainment industry, breaking down racial barriers in many previously segregated venues. During World War II, the two tried to organize performances for servicemen, but they were rejected due to the prevailing segregation in the U.S. Armed Forces, despite a recommendation from Eleanor Roosevelt.

As “Fare Thee Well,” “Dink’s Song” was among a half dozen songs Holman and White recorded for Decca in 1942. Three years later, White recorded the tune again on his first solo album, Songs by Josh White, for Asch Records, a predecessor of Folkways. He recorded it at least once more later in his career, on the 1957 Mercury album called Josh White's Blues.

Our Take on the Tune

In the Floodisphere, Randy Hamilton has reinvented this century-old tune into something as fresh and sweet as a summer breeze.

And if listening to it has you hankering for more music from Randy, just swing on by the free Radio Floodango music streaming service and tune in the Randy Channel.

Share this post