Singer/songwriter Bob Gibson was a defining figure in the folk music revival starting in the late 1950s, but a crushing dependence on heroin and other drugs sank his career, his marriage and many of his long-time friendships.

Gibson — who wrote songs like “Abilene” and “There’s a Meeting Here Tonight” that were performed by artists such as Peter, Paul and Mary, The Limeliters and Simon and Garfunkel, as well as The Byrds, The Smothers Brothers and others — hit rock bottom in the late ’60s.

The Road Down

“I left the business in ’66,” Gibson wrote in his autobiography, I Come for to Sing. “It seemed to me working in clubs, being on the road, being in show business and around musicians caused me to use drugs. I thought if I got away from that, everything would be fine.”

To that end, he spent almost three years in a country hideaway with his young family trying to get clean, but ultimately, he wrote, the hiatus failed its mission.

The early 1970s found Gibson relocating again, this time to the West Coast, commuting for occasional gigs in clubs in Chicago and Los Angeles. “I was just hanging in,” he wrote, “doing the same set of songs, and I wasn’t writing or learning.”

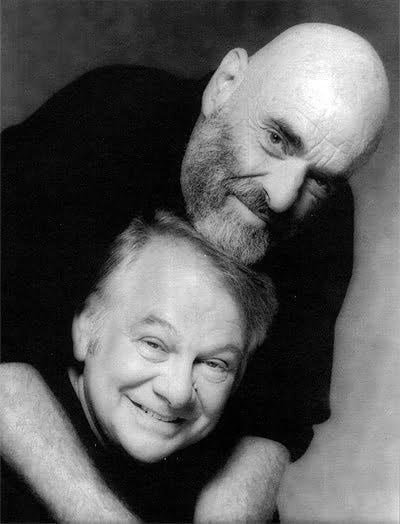

Enter Shel

But then he reconnected with an old friend — writer/artist Shel Silverstein — who helped “in jarring me out of this,” Gibson said. “Shel would come up there and we’d write songs.”

Meanwhile, what he called “a classic music business snafu” torpedoed his last major label release, so in 1974 — re-energized by the songs he had written with Shel — Gibson started one of the country’s first-ever artist-owned record companies. In those days, his new Legend Enterprises label was a novel approach to making records.

Bob’s Funky In The Country was its first release, recorded live at the legendary Amazingrace Coffeehouse in Evanston, Ill., near Chicago.

Buoyed by a rave review in Billboard magazine, the album gave the fledgling label a fine start, but it was quickly undermined by Gibson himself: The first stop on the road to promote his new album was a few months in rehab. By the time Bob was ready to travel again, the momentum had moved on.

The Song

A highlight of that lovely album — “Two Nineteen Blues” — is built around Gibson’s imaginative reworking of several long-standing blues motifs.

His chorus (“I'm going down to the river / Gonna take along my rocking chair”) comes from well-known versions of “Trouble in Mind” as sung by everyone from folkie Cisco Houston to soulful Sam Cooke to country’s Johnny Cash.

And the song’s hook (“Gonna lay my head down on some lonesome railroad line / And let the two-nineteen come along and pacify my mind”) has even deeper blues roots.

No less an authority than the great Jelly Roll Morton said “Mamie’s Blues” — from which the line comes — was “no doubt the first blues I heard in my life. Mamie Desdunes, this was her favorite blues. She hardly could play anything else more, but she really could play this number.”

Desdunes (sometimes written Desdoumes) was a well-known singer and pianist in “The District,” as New Orleanians called the area now generally remembered as “Storyville.”

What’s in a Name?

Blues historian Elijah Wald notes the old song’s title is often given as “2:19 Blues,” as if referring to a train time; however, jazz historian Charles Edward Smith recalled Morton explaining that the 219 was the train that “took the gals out on the T&P (Texas and Pacific railroad) to the sporting houses on the Texas side of the circuit.”

Despite all its lyrical borrowings from blues antiquity, “Two Nineteen Blues” is unmistakably a Bob Gibson creation. He brought to it a completely new melody and fresh lyrics brimming with his trademark sass and winking understatement. For example, Bob sealed the deal in a final verse that finds his antagonist in a small-town jail, where:

I hit the judge and I run like hell

And the sheriff he’s still askin’ ‘round ‘bout me.

Our Take on the Tune

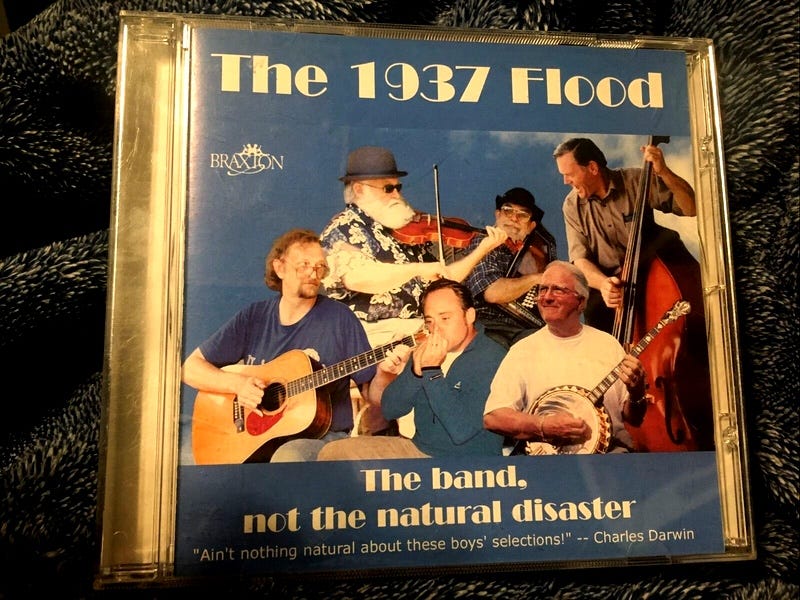

For folks who know The Flood only from its studio albums, this is the first tune they may have ever heard from the band.

That’s because this rollicking composition was what the guys played on the opening track of their very first commercial album nearly a quarter of a century ago now. And speaking of names, because of a design error, the song was erroneously listed on that inaugural album as “Rocking Chair,” a name it has retained in the Floodisphere ever since.

A lot changes in a band over the decades, but good old tunes — under whatever name — are like cherished letters from home. Here’s a version from a recent rehearsal.

Share this post