The mood can change very quickly in The Flood band room, often depending on whatever is the next song that crosses Charlie Bowen’s rattlin’ brain.

For instance, in the first few seconds of this week’s podcast, you’ll hear the guys still laughing from the inside jokes and joys of the previous tune, while Bowen is ready to conjure up a more somber mood with some opening chords.

Almost at once, Danny Cox and Randy Hamilton recognize the lead-in and join in on the 1950s torch song, “Cry Me a River.” Seconds later, Jack Nuckols is slapping a rhythm and Sam St. Clair is offering moody accents.

Anything But Plebeian

The story of this song’s troubled childhood — rejected in its first bid for movie stardom, initially passed over by the queen of jazz ballad, etc. — in an earlier post, but let’s take another swing at it, this time focusing on a single word in its otherwise rather pedestrian lyrics.

The bridge of “Cry Me a River” contains what writer Molly Leikin, in her book How to Write a Hit Song called “the best multisyllabic internal rhyme I’ve heard.” Specifically, the song rhymes:

You told me love was too plebeian

with

Told me you were through with me’n’…

“‘Too plebeian’ and ‘through with me’n’,” Leikin wrote, “are just as delicious now as when they were first written. This quadruple rhyme isn’t just four syllables that rhyme, but four unique syllables.”

But Jack Said No, And So Said Mitch

Cool enough, but it was not everybody’s cup of tea. In fact, plebeian (which, of course, is a snooty way of saying “commoner”) was just too highfalutin for many show biz folks.

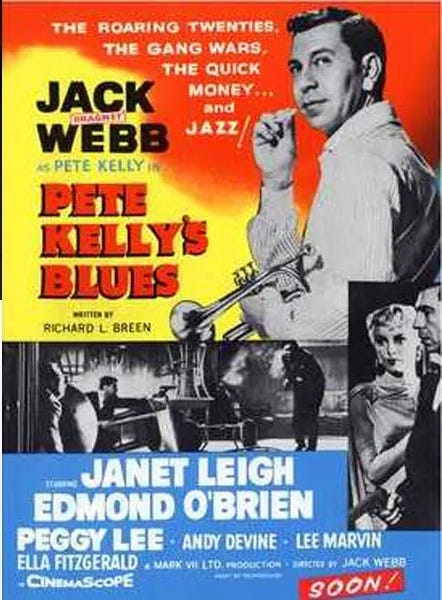

For instance, director Jack Webb originally wanted the song for his 1955 movie Pete Kelly’s Blues, but he hated the use of the word and when songwriter Arthur Hamilton refused to change it, Webb yanked the song from the film.

The lyric had no better luck at Columbia Records where the A&R chief — one Mitch Miller (of early TV’s “Sing Along with Mitch” fame) — joined the plebeian haters and blocked it from being recorded there by Peggy King.

The Stubborn Songwriter

Still the songwriter stood his ground and refused to change his lyric.

Wonder why, given the riches promised to Hamilton by having his song included in a Hollywood film? Well, writer John E. Simpson in his online newsletter “Running After My Hat,” has an intriguing theory.

As noted in the earlier Flood Watch article, 27-year-old singer and aspiring actress Julie London, who would ultimately record “Cry Me a River” and have a monster hit with it, was married to Jack Webb at the time he would working on Pete Kelly’s Blues.

When Webb thought it would be a great idea to have some original songs, not just old standards, wife Julie remembered Arthur Hamilton. He was a young guy she’d graduated from high school with; in fact, he’d taken her to the senior prom.

She and Arthur had drifted out of touch since their school days in the mid-1940s, but Julie remembered he’d wanted to be a songwriter. She gave him a call, asked if he was still writing music.

“I was,” Hamilton recalled years later, “but I was writing them on the backs of prescription blanks, working as a delivery boy for a prominent drugstore chain.”

When got the call from Hollywood, Hamilton cranked out three tunes — “He Needs Me,” “Sing a Rainbow” and (ta-duh!) “Cry Me a River” — the first two of which Webb used in the picture, but then Webb blocked the winner of the bunch because of Hamilton’s refusal to change that problematic rhyme.

Was It Code?

So, again, why?

“I’ve got my own pet theory about this,” Simpson writes in his newsletter, “completely unsupported by anything except speculation and a taste for intrigue: I wonder if the word ‘plebeian’ was an in-joke of some kind between Hamilton and London? Lord only knows what sort of in-joke it would be. But it’s a fun idea, isn’t it?”

Indeed.

Share this post