Our version of this traditional tune originated with Roger Samples and the quiet picking sessions he and Charlie Bowen had back in the mid-1970s.

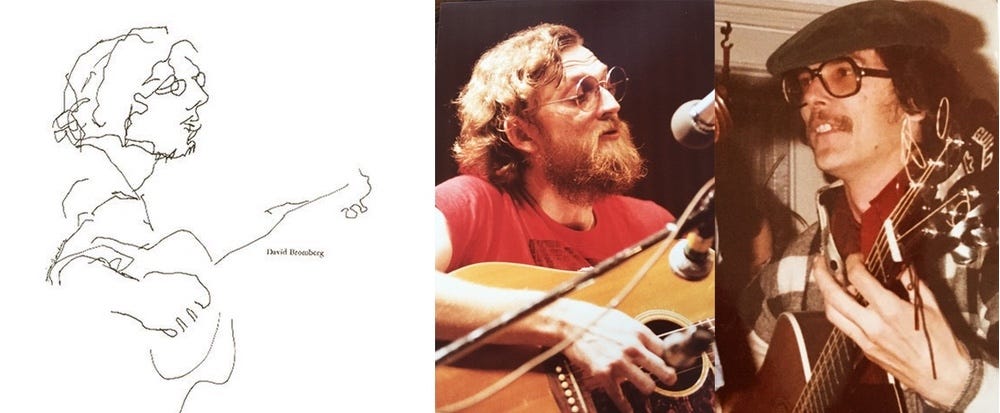

They had been listening to David Bromberg’s then-new debut album, on which they both liked Bromberg’s arrangement of something that Philadelphia folkie called “Dehlia.” But of course, as usual, Samples had his own ideas for the song.

Crafting a new melody that he borrowed from assorted sources — versions had been recorded over the years by everyone from Blind Willie McTell and Blind Blake to Pete Seeger and Josh White, from Harry Belafonte and Burl Ives to Johnny Cash and Bobby Bare — Roger then turned the lead vocal over to Charlie so he could sing the harmony himself on the choruses.

Their resulting rendition of “Delia’s Gone” made the rounds at the Bowen Bashes and put in regular appearances at occasional Flood gigs. But eventually, the song was retired.

And it remained so for the next several decades, until one night earlier this summer. That’s when the tune popped into Charlie’s head during a weekly rehearsal. Right from the start, Danny, Randy and Sam were giving new life to the old number. It looks like it’s back to stay.

Murder History

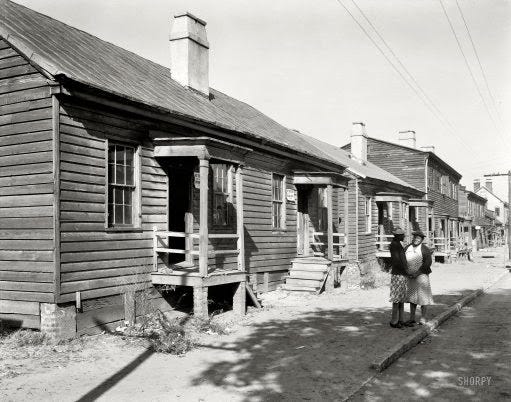

The story behind “Delia’s Gone” begins on Christmas Eve 1900, when Moses "Cooney" Houston shot and killed Delia Green in the Yamacraw neighborhood of Savannah, Georgia. And if that isn’t tragic enough, both were just 14 years old.

Legend has it the two had been fussing all evening during a Christmas Eve party at the home of Willie and Emma West, where Delia worked as a scrub girl.

Delia and Cooney had been going together for several months. Folks say that night the quarreling started when a very drunk Cooney began teasing Delia about their having sexual relations. Perhaps, some say, he was just trying to embarrass her in front of the Wests.

At some point, according to trial transcripts, Delia got angry at being characterized as Cooney’s wife, and she cursed him, calling him a “son of a bitch.” Sensing a situation that was getting out of hand, the Wests ordered Cooney to leave. That’s when Cooney pulled a pistol.

After shooting Delia, he fled, but Willie West chased after and caught him. He turned Cooney over to a police patrolman who later testified that the young assailant confessed.

Houston served 12 years in prison, paroled in 1913. Accounts of his later life are sketchy, but he is said to have died in New York City in 1927 after other brushes with the law.

Delia Green is buried in an unmarked grave in Savannah.

The Song

If it hadn’t been for a song, Cooney and Delia’s sad story surely would have been quickly forgotten.

However, as early as 1906, folklorist Howard Odum collected a fragment of the ballad in Newton, Ga., and published it in The Journal of American Folklore. This version — a three-verse fragment called “One More Rounder Gone” — implied that Delia was a prostitute. That insinuation was to move in and out of other renditions in the years to come.

After that, the ballad traveled from Georgia to the Bahamas, then back to the States during the folk boom of the 1950s and ‘60s, sung by generations of balladeers and recorded by musical icons like Bob Dylan and Johnny Cash.

In 1928, Newman Ivey White’s American Negro Folk Songs included a five-verse variant called “Delie,” collected four years earlier from Frank Goodell of Spartanburg, SC, who reported that he learned it sometime around 1904.

The first recording of the song was by Georgian Reese DuPree in the winter of 1924.

(If you’ve heard of DuPree, it’s probably because he’s widely recognized as the first African-American male to record a blues. Incidentally, he’s also generally credited with writing the song, “Shortnin’ Bread,” which he was singing in public as early as 1905.)

But back to Delia and Cooney. Early versions of the song like "One More Rounder Gone" and "Delia" were originally accompanied by the traditional "Frankie and Albert" tune.

But when the song made its way to the Bahamas, new lyrics were added, and the tune took on a decidedly Caribbean flavor. As early as 1935, Alan Lomax recorded a local version in the Bahamas by the renowned Nassau String Band.

Curiously, most subsequent versions of the song would use that form rather than one based on the song’s older, original American cousin.

Share this post