One of the most curious and complicated characters on the great American musical landscape is Thomas A. Dorsey.

A deeply religious man, Dorsey often is called “the father of gospel music,” because he inspired a movement that popularized bluesy gospel songs in churches across America starting in the mid-20th century.

Some 3,000 songs — a third of them gospel — were written by Dorsey in his 90 years, including “Take My Hand, Precious Lord” and “Peace in the Valley.”

Now, then, about those other 2,000 songs ….

Recording as “Georgia Tom,” Dorsey also was instrumental in the early days of secular blues. With his partner “Tampa Red,” he helped popularize the sexy, happy hokum music of the 1920s and ‘30s with tunes like “Somebody’s Been Using That Thing,” “Dead Cat on the Line.” and “The Duck — Yas, Yas, Yas.”

In the Beginning….

Born in the rural Georgia town of Villa Rica, Dorsey grew up in a religious family, but gained most of his musical experience playing blues piano at barrelhouses and rowdy parties in and around Atlanta, where the family moved when Thomas was eight years old.

As a young man, Dorsey began attending vaudeville theater shows that featured blues musicians, with whom he informally studied. Despite being meagerly compensated for his efforts, Thomas played at rent parties, house parties and brothels.

Seeking a greater challenge, in 1919 Dorsey moved to Chicago, where he discovered that his brand of playing was unfashionable compared to jazz’s newer uptempo styles. Faced with more competition for jobs, Dorsey turned to composing. In 1920 he published his first piece, called "If You Don't Believe I'm Leaving, You Can Count the Days I'm Gone,” making him one of the first musicians to copyright blues music.

Dorsey also copyrighted his first religious piece in 1922 (a song called “If I Don't Get There"), but he quickly found that sacred music could not financially sustain him, at least not in the Roarin’ Twenties, so he continued working the dives and playing the blues.

Enter Ma Rainey

Dorsey’s big break came in 1923 when he was hired as the pianist and leader of The Wild Cats Jazz Band accompanying Ma Rainey, a charismatic and bawdy blues shouter who by then had been performing professionally for 20 years.

When Rainey and The Wild Cats opened at Chicago's largest black theater, Dorsey remembered the night as "the most exciting moment in my life,” according to his biographer Michael W. Harris.

Dorsey worked with Rainey and her band for two years, composing and arranging her music in the blues style as well as vaudeville and jazz to please audiences' tastes. Often at his side was a new member of the band, Hudson “Tampa Red” Whitaker, a blues guitarist who in 1928 would become Dorsey’s recording partner for five years.

Rainey enjoyed enormous popularity touring with her hectic schedule, singing about lost loves and hard times. She interacted with her audiences, who were often so enthralled they stood up and shouted back at her while she sang.

But Dorsey increasingly had misgivings about the suggestive lyrics of the songs he and Red were writing. Finally, Thomas left the tour and tried to market his new sacred music. He printed thousands of copies of his songs to sell directly to churches and publishers, even going door to door, but he still couldn’t make it work.

About This Song

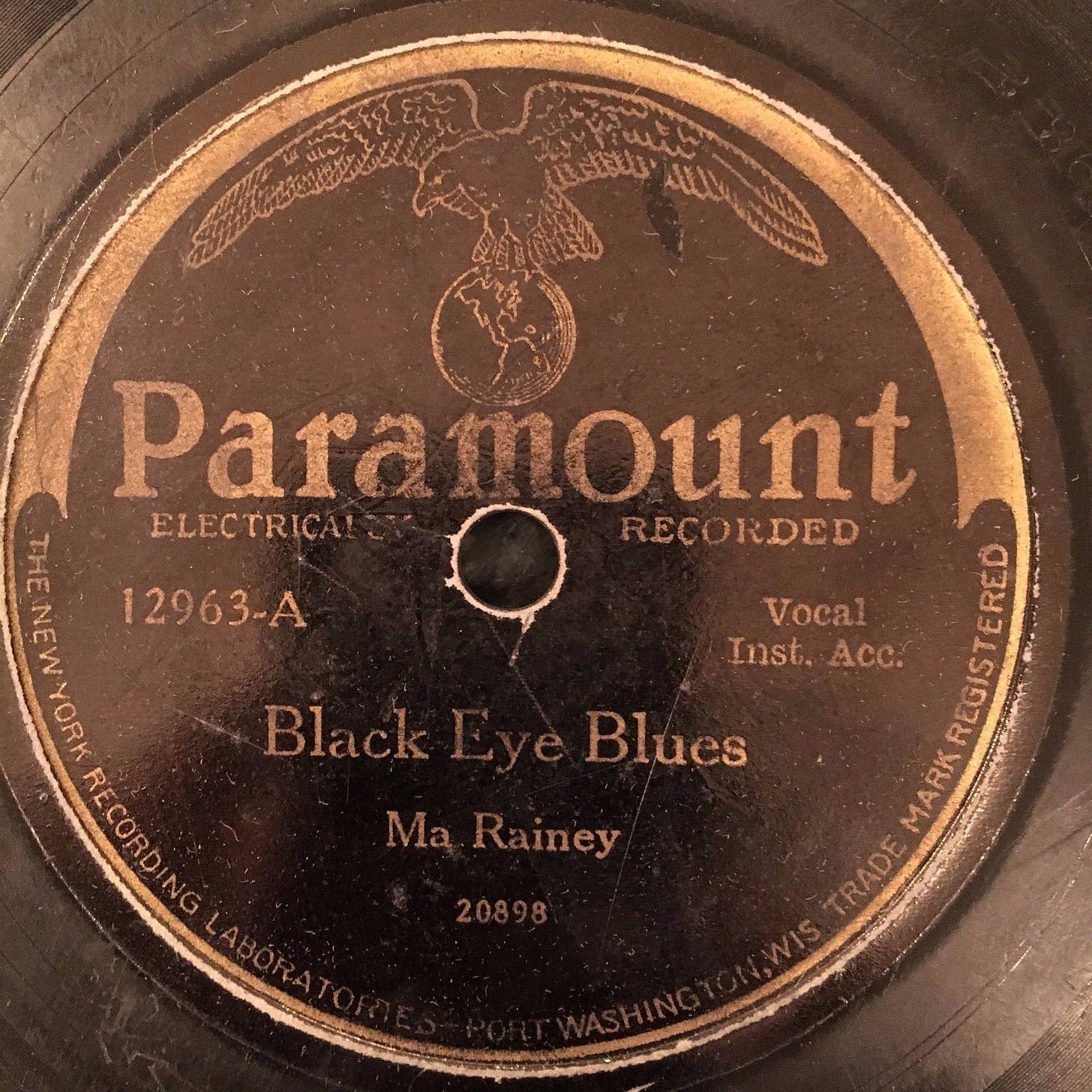

Dorsey returned to the blues in 1928, but this time in the recording studios in the persona of “Georgia Tom.” The first Paramount sessions for him and Tampa Red were the last ones for Ma Rainey. In fact, one of the last things the great blues singer ever recorded was this new Thomas Dorsey composition.

Nowadays for vinyl collectors, Rainey’s “Black Eye Blues” is a rare find. That’s because Ma’s September 1928 recording of the song wasn’t released until July 1930. By then, the Great Depression was raging. Rainey had left the business (retiring to her Columbus, Ga., home). Paramount was ending too; the studio ceased operation in 1932.

While audio of the record was later preserved on blues compilation albums (and now on YouTube), the song itself has had a sketchy history. Over the years, the controversial subject matter — domestic violence — has made it uncomfortable for many singers to tackle, especially when dealing with Dorsey’s no-compromise lyrics:

You low-down alligator, you watch and sooner or later

I’m gonna catch you with your britches down!

When folkie Judy Henske recorded it in 1964, for instance, her producers at Elektra changed the title to "Low Down Alligator.”

Similarly, when Odetta recorded the song two years earlier, she also found the title a bit too much for early 1960s sensibilities. On the Riverside label, instead of “Black Eye Blues,” the song was listed as “Hogan’s Alley,” based on Dorsey’s opening line (Down in Hogan’s Alley lived Miss Nancy Ann….)

Hogan’s Alley

Which raises a question. Where is “Hogan’s Alley,” anyway?

Many cities (from Vancouver to Virginia) have one, but historian Robert Lewis Miesen writes, “Rather than being the name of a person, ‘Hogan’s Alley’ was a derogatory 19th century label, much as one might use ‘skid row,’ ‘ghetto’ or ‘hood’ today.”

He noted that in the same spirit back in 1895, artist Richard F. Outcault — father of the modern comic strip — placed his “Yellow Kid” character in his “Hogan's Alley” cartoons, which appeared weekly in The New York World, starring rambunctious slum kids in the streets.

Our Take on the Tune

Meanwhile in Floodlandia, when the whole band can’t get together — like last week, when it was just Danny, Randy and Charlie — it’s an opportunity to lay back and explore tunes not usually on the practice list.

In Flood years, this song dates back nearly a half century, to when the fellows were first starting to fool with the hokum tunes of the 1920s and ‘30s.

Here’s “Black Eye Blues” from last week’s gathering.

Share this post