This is the story of a song’s evolution from ragtime composition to folk song, then from blues to bluegrass.

We begin in 1900. Danish-born American violinist/composer Jens Bodewalt Lampe, inspired by Scott Joplin’s hot new “Maple Leaf Rag,” composed his own syncopated piece, which he called “Creole Belles,” published in Detroit by Whitney-Warner.

A child prodigy (he became the first chair violinist for the Minneapolis Symphony when he was just 16), Lampe was exploring this exciting new type of music. What later came to be called “ragtime” was at the time variously described as “cakewalk,” “march” or “two-step” music.

Lampe’s “Creole Belles” was a hit, performed widely by pianists, ragtime bands, brass bands and military bands. In 1902, when John Phillip Sousa championed this piece by recording it, Lampe became one of the country’s best-known ragtime composers, second only to his hero, Joplin.

The Evolution Begins with The Fiddlers

Lampe’s work had one of the most amazing cultural cross-pollinations in music history.

The catchy melody of the second section or strain of “Creole Belles” first was picked up by fiddlers, who also adopted alternative names for their newly borrowed tune, including “Back Up and Push,” “Rubber Dolly” and “Rubber Dolly Rag.”

Then came the string bands. The tune was so popular with them, in fact, that most Appalachian bands that were recording in the 1920s and ‘30s released some version of it.

Under the title “Back Up and Push,” the song was recorded twice in mid-1929, just days apart. It was waxed in Richmond, Indiana, by a little-known group called The Augusta Trio, then in Atlanta by a fiddle band with the unlikely name of “The Georgia Organ Grinders.”

Five years later, the better-known Gid Tanner and The Skillet Lickers did the song in San Antonio for Bluebird.

Meanwhile, the earliest version in which the tune was called “Rubber Dolly Rag” was recorded by Uncle Bud Landress for Victor, also in Atlanta, in November 1929.

The song broke out of the hillbilly genre with a 1931 Columbia Records release by Perry Bechtel and His Boys. (Bechtel, a virtuoso guitarist and tenor banjoist, called it “Little Rubber Dolly.”)

Footnote: In 1926 banjoist Charlie Poole and his North Carolina Ramblers used the same melody for “Goodbye Booze,” itself based on a 1901 novelty vaudeville number by Jean Constant Havez.

The Blues and Folk

Meanwhile, the melody was ready for yet another evolutionary turn.

Beloved blues guitarist and singer Mississippi John Hurt, who in the early 1920s often collaborated with fiddler Willie Narmour, brought Lampe’s original title back to the forefront by adding lyrics, calling it “My Creole Belle” and giving it a smoother new rhythm.

Hurt sang:

My Creole Belle, I love her well

My darling baby, my Creole Belle

When the stars shine, I’ll call her mine

My darling baby, my Creole Belle.

Known for playing square dance and ragtime music during the same period that he was recording early blues for Okey Records, Hurt’s interest in different musical styles meant the melody was heard by a much wider audience. (Incidentally, Hurt also used essentially the same tune for his “Richland Woman.”) Subsequently, Woody Guthrie and other folkies were to record it as “My Creole Belle.”

Swing (Western and Otherwise)

Soon Western swing bands and Texas-style fiddlers popularized four or five versions of the tune with characteristic dance rhythms.

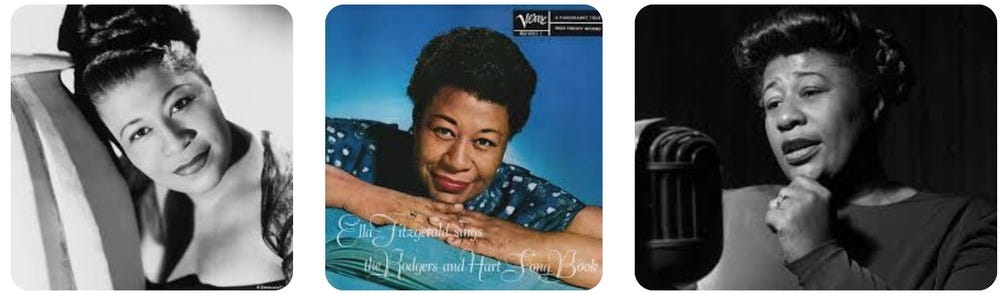

And in 1939, Ella Fitzgerald and The King Sisters each released "Wubba Dolly" with novelty vocals.

Bluegrass and Beyond

When bluegrass and early rock developed, each genre gave the song still more new treatments. For Bluebird, for instance, Bill Monroe recorded an instrumental version in 1940.

Fiddler Tommy Jackson brought out his take in 1951, followed by The Stanley Brothers and then by …. well, by everybody.

Finally, there were rock renditions. Curiously, for example, 10 years after Bill Black died, the Bill Black Combo still was touring, and the group charted as late as 1975 with “Back Up and Push” on its World's Greatest Honky Tonk Band album.

Our Take on the Tune

Danny Cox learned his version of the song from a recording by his hero Chet Atkins on the 1965 More of That Guitar Country album. This Flood track was recorded at a recent gig at Sal’s Speakeasy in Ashland, Ky.

Here you’ll hear Dan and harmonicat Sam St. Clair trading choruses on the tune as we call folks back to the bandstand to begin our second set.

By the way, The Flood will be back at Sal’s next week. We’re playing Saturday, April 22, from 6 to 9, and, as a special treat, our dear friend, Floodster Emerita Michelle Hoge, will be back as the evening’s guest artist. Come on out and party with us!