Of all the tunes we do, none is more evocative than “Autumn Leaves.”

Joseph Kosma’s post World War II composition quickly became a jazz standard in America from the 1950s right up to today.

“Autumn Leaves” actually is the tale of two torch songs,” music journalist Bill DeMain notes. “The original, written in French as “Les Feuilles Mortes” (meaning, “Dead Leaves”), was a dark lament of lost love and regret.

“The translated version,” DeMain says, “ touched on the same theme, but in a gentler, more wistful way.”

Poetic Birth

It started as a poem written in 1945 by screenwriter and Left Bank intellectual Jacques Prévert as part of the script for a ballet called Le Rendezvous.

Two years later, when director Marcel Carné made a film of the ballet, Kosma entered our story, setting the Prévert verse to music.

“Maybe because the words weren’t conceived in song form,” says DeMain, “it took on a slightly unwieldy structure. Kosma interpreted it as 24 bars of introductory verse containing two distinct moods and melodies, followed by a 16-bar refrain (half the length of a traditional Tin Pan Alley song).”

Carné’s film was a flop, but the song had a life of its own. The movie’s lead actor, a popular young singer named Yves Montand, made it his.

But it was French chanteuse Juliette Greco — the perpetually black-clad “Little Miss Existentialist”— made perhaps the most memorable French version.

In 1950, when the song was translated into English with Johnny Mercer lyrics, only a small part of the original opening verse survived (and is rarely sung today).

“Mostly,” notes DeMain, “it became about featuring the catchy, spiraling 16-bar refrain. … In effect, this was a completely different song from the rambling elegy Prévert and Kosma had created. While the original was about an all-consuming passion, this was more about a fleeting attachment. More nostalgic than angst-ridden, more bittersweet than bitter.”

Coming to America

Five years later, Nat “King” Cole took it to No. 1 on the hit parade, making it a nightclub standard for everyone from Frank Sinatra to Tony Bennett and Eartha Kitt.

In 2012, jazz historian Philippe Baudoin called the song "the most important non-American standard."

"It has been recorded about 1,400 times by mainstream and modern jazz musicians alone,” Baudoin said, “and is the eighth most-recorded tune by jazzmen.”

Notable versions have been recorded by Miles Davis, Stan Getz, Chet Baker and Erroll Garner, by Ahmad Jamal, Duke Ellington and Cannonball Adderly, by John Coltrane, Chick Corea and Stanley Jordan.

Our Take on the Tune

This song has those marvelous Mercer lyrics, as Floodster Emerita Michelle Hoge demonstrates whenever she’s in the room. But when she’s not here to sing it, the song also is an extraordinary vehicle as an instrumental.

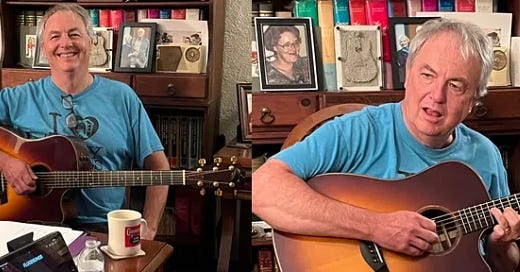

Here from last week’s rehearsal, Danny Cox lays down that lovely melody, then his old friend and our guest for the evening — Bob Murnahan, in town for a visit from his Colorado home — takes a couple of choruses to mine gold in all those cool chords.

Share this post