New Music for a New Year

#165 / Flood Time Capsule: 1974

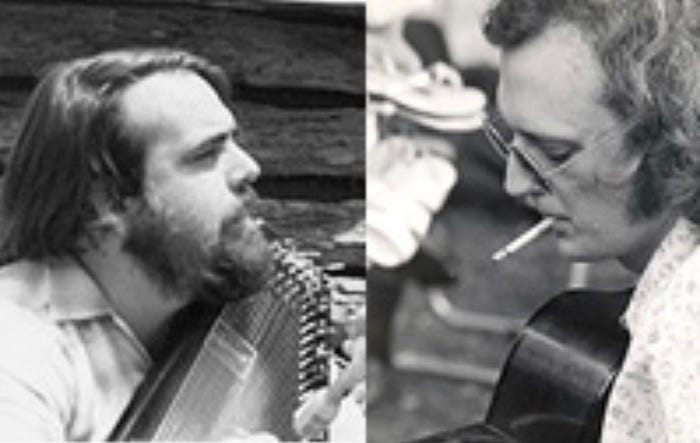

At a New Year’s Eve party in 1973, David Peyton and Charlie Bowen sang their very first song together.

The tune they chose was one that married Appalachian balladry and African American blues roots (as well as a little northern and southern history). In other words, the song rather appropriately presaged the eclectic repertoire that Dave and Charlie would bring together as The 1937 Flood got its start in that new year.

Peyton always thought it was fitting how a band that loves to party was born at a party at his house.

Anyway, that night, as they figured out what songs they knew in common, Dave and Charlie realized they each had learned this one from very different sources and with very different titles.

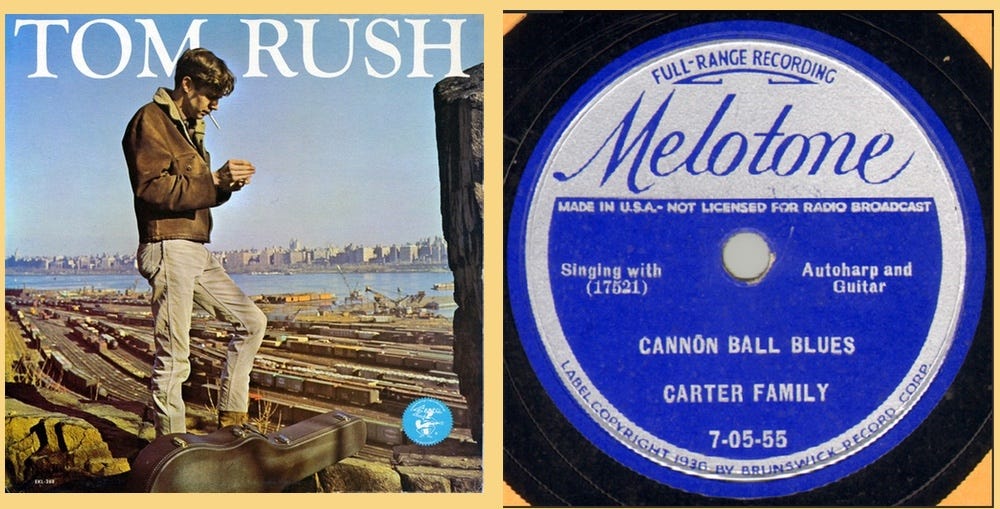

To Peyton, the song was “Cannonball Blues,” recorded in the 1930s by his heroes, the great Carter Family. To Bowen, on the other hand, the same song was called “Solid Gone” and was recorded in the mid-1960s by one of his favorite folksingers, Tom Rush.

“What key you want?” Charlie asked.

Dave hummed it, strummed it and then summed it up.

“C,” he said.

On guitar, Charlie tried out a few bars from memory. On his Autoharp, Dave jumped in with a little harmony. Meanwhile, across the room, Pamela Bowen pushed the buttons on her tape recorder. That’s why we have — straight from the wee hours of Jan. 1, 1974 — this bit of stumbling antediluvian audio:

The Cannonball Story

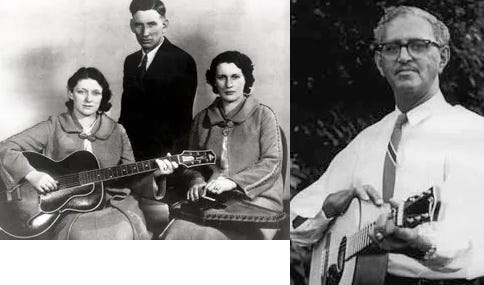

As “Cannonball Blues,” the song has the ultimate stamp of Appalachian authenticity, recorded not once but twice by The Carter Family, first in 1930, then again in 1935. In addition, the song has decidedly African American credentials as well, because of how it was collected.

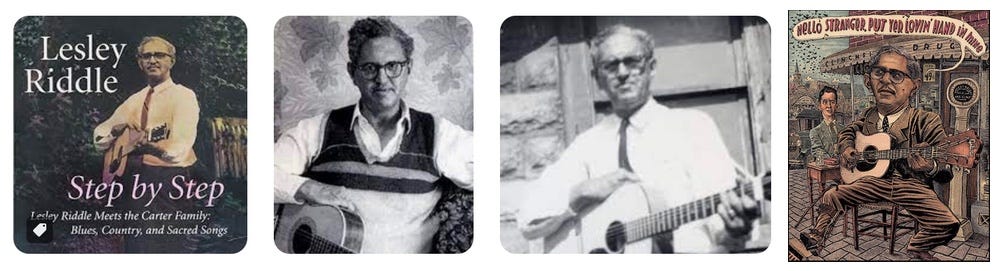

A.P. Carter learned “Cannonball Blues” in 1928 from his long-time friend, Leslie Riddle, who in turned learned it from his uncle.

Carter and Riddle were an unlikely pair in 1920s Virginia. Eschewing some people’s probable disapproval of a mixed-race partnership, the two men traveled together extensively on song-collecting trips throughout the Appalachian South.

As the pair discovered tunes, A.P. wrote down the lyrics they heard and Leslie (he was often called “Esley” in contemporary accounts, incidentally) committed the music and melodies to memory. Their collecting expeditions produced many hits for later Carter Family recordings.

In addition, it was Leslie Riddle who taught Maybelle Carter how to play her distinctive Carter Family guitar strum.

Riddle was living in nearby Kingsport, Tennessee, and “he’d come over and stay for weeks at a time and help us all he could,” Sara Carter said later. “He was a good guitarist, and he was a good singer. We learned the way he picked …. Maybelle kind of caught some of her style from him,” Sara added.

White House Blues

The melody that Riddle sang for “Cannonball Blues” was not original; on the contrary, the same tune was used by other musicians who penned their own lyrics, especially in the blues community.

Furry Lewis, for instance, used it in 1927 for his “Billy Lyons and Stack O'Lee,” while in the following year Mississippi John Hurt sang his “Frankie” to it.

But one of the earliest and best known players of the melody was Charlie Poole in his “White House Blues,” which he recorded in 1926 for Columbia with The North Carolina Ramblers.

Poole — destined to be another of The Flood’s lifelong heroes — almost certainly didn’t write the song; instead, he likely learned it in his travels through the South. Poole was, though, the first to get it on to disc.

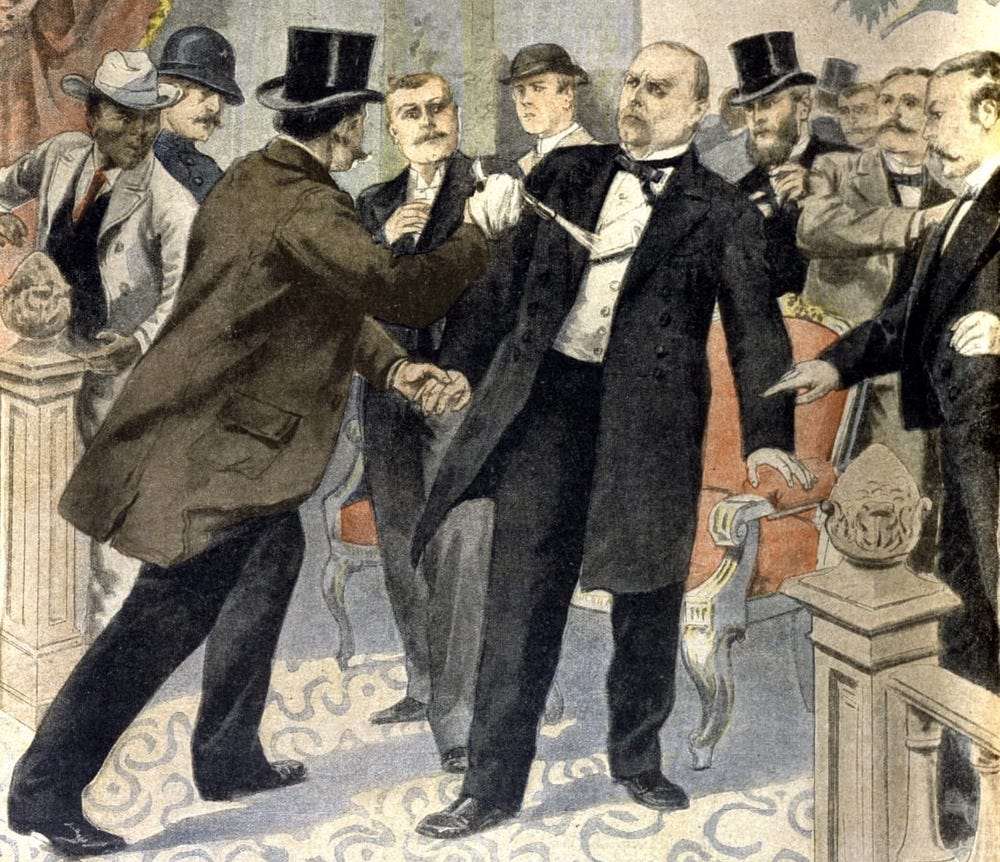

Offering a sardonic — okay, a downright jaunty — report on the 1901 assassination of President William McKinley in Buffalo, NY, “White House Blues” probably was performed with a wink and a nod by many string bands in the South, where McKinley had been … well, not especially popular. (“Hey Mr. McKinley,” says one verse, “why didn't you run? See that man a-comin' with a Johnson Forty-One… from Buffalo to Washington.”)

Add Solid Gone

The final piece of the patchwork tune that Dave and Charlie played together on that 1974 winter’s night came from folksinger Tom Rush.

As noted, when Rush recorded his own version of the tune, he called it “Solid Gone.” That’s because he added a chorus to the traditional “Cannonball Blues.” Those eight bars were a slight variation on what Mother Maybelle herself rendered for “He’s Solid Gone” for the flip side of her 1953 re-recording of “Wildwood Flower” with The Carter Sisters.

Tom did some gender-switching, though, singing the chorus as, “I'm down here cryin' 'cause she's gone, feel like I'm dying' 'cause she's gone, solid gone.”

Our Take on the Tune

So, this was the musical amalgamation — a bit of white and black Appalachia, a bit of northern history and southern hijinks, filtered through a bit of 1960s folk style — that Dave and Charlie took as their first song together a half century ago.

“Solid Gone,” as we have always called it, has continued in The Flood’s repertoire over the decades. And, coming full circle, 40 years after that first performance at the party where The Flood was born, the song finally made it onto a Flood album.

It’s featured on Clean Up & Recovery , with Randy and Michelle joining Peyton and Bowen on the vocals and with solos by Joe, Doug, Sam and, of course, Dave. Click button below to hear that 2013 version: